Sorry for the posting delay. Life took a turn for the hectic lately. Hopefully I'll get some new art up by Easter. If I can get my spare room cleaned up, I can get to my easel again and start work on the commissions that I've been, well, commissioned to do. Oh, and Kane and Anonnunimust B., I haven't forgotten you guys. Kane, I've been too busy to really ponder your question adequately, and Anon., I'm coming up empty on a clear definitive statement on St. Thomas' understanding of Allah's identity, other than what I had given you initially in the Q&A combox. I'm still looking, though.

After I "swam the Tiber", so to speak, six years ago this Easter (Wow! Already?!) I "lost touch" with a number of my friends from my old Pentecostal church and Bible College. Some of them simply drifted out of my life the way people do, but for many, I'd always suspected that my "poping" was a key (if not the key) factor in many of my friendships evaporating almost overnight.

Now, of course, only one or two of the gutsier of them actually came right out and admitted that my conversion was a detriment to our friendship (and, ironically, they're the ones that I do still communicate with, at least from time to time). But for the rest of those former friends and colleagues and classmates who've committed themselves to "radio silence", I'd always suspected that their reason for doing so was that I was now a Catholic. Suspected, but could never really prove. Occasionally, I chastised myself for having a "martyr's complex" about it, because people will ask me about my conversion, my reasons and my story, and what the fallout was. And they'll look at me incredulously when I say that I suspect that a good number of my friends don't talk to me anymore because of my conversion. "That's crazy!" they'll say. "I can't believe they would do that." Truth is, neither could I.

Then, dear friends of mine got married. On their return from their honeymoon, they decided to try a new church. This church happened to be attended by an old Bible College classmate of mine (and of the bride's, for we went to school at the same time). So after the service, she took a few minutes to catch up with this mutual friend of ours, and later on, called me to tell me about it.

'Cause, you know, I happened to come up. My friend asked this fellow if he ever talked to me at all, and, she told me, his response was, "Well, he became Caaath'lic. At first, I tried to say my piece, and he didn't receive it all that well, so, y'know..."

At this, my wonderful friend went to bat for my wife and me, saying, "Oh, well, his wife is my best friend!" In other words, what the hell does denominational affiliation have to do with friendship? I mean, okay, sure, the differences of opinion that come from different beliefs can obviously strain a relationship. But to utterly cut a friend out of your life because he disagrees with you about religion? And the ironic thing is, this person and I were never in agreement when we were both Protestants! But I guess at least then, our one thing in common was our protest against Rome--and that protest trumps all other issues of faith and morals for some people.

I've written all this, not because I'm bitter at this person, or, again, not because I want to play the martyr card ("O woe is me! All my friends hate me, I might as well go eat worms!"). Quite honestly, if my Catholicism is so offensive to you that you have to choke it out like it's a lamentable deformity or contagious plague, then by all means, please beware! Unclean! Unclean!

I suppose there are two points I want to make in writing this: The first is, I'm not sick. Hanging out with me won't infect you with incurable papism--well, unless you're the sort of open-minded person who actually wants to engage in rational dialogue. Then I make no guarantees. In all, I'm still by and large the same person I used to be. The differences that have come about, I hope, are for the better. If not, then who better to let me know than my friends. 'Course, you'd actually have to talk to me to find out.

The second point I want to make is that we've entered the season of Lent. For the majority of my readers, that means, I suppose, meditating on Christ's passion, making sacrifices to more closely identify with Him, and eating fish and chips on Fridays. It's also that time of year when adults considering conversion make that final lap in RCIA, heading to the home stretch before the Easter Vigil finish line (or starting line?). As much as I love you all and encourage you in your journeys to the Catholic Church, I want to make sure that the blinders are off--that you've counted the cost. For many, it's a simple transition, with friends and family on the other side waiting to welcome them home. For many others, it means leaving friends and family behind, feeling wounded and abandoned.

The Catholic Church shows its wisdom in the RCIA process--a nine month journey of investigation and instruction before full reception into the sacramental life of the Church. Not only does it help to prepare the new convert, it gives a gestational period in which, hopefully, those affected by the convert's decision can grow to understand and maybe accept this decision, and even, hoping against hope, join the convert on his journey. Nevertheless, the joy of new birth into the Catholic Church is often tainted by a post-partum depression for the new convert and for those on the far bank of the Tiber River.

For many people on the outside, Richard Dawkins's assessment of the Catholic Church as the greatest force for evil in the world rings absolutely true (though I can't fathom how one purports to back up that assertion--especially in a scientifically empirical manner as Dawkins should be held to as a scientist--but that's an article for another time). Many times, the convert's friends and family can't conceive of them actually wanting to become Catholic. The issue, however, is often such a sensitive one, that they won't actually want to debate you or hear your reasons and justifications for the Church you've grown to love, and your decision to join it. They seem to prefer to speculate on your behalf--reasons ranging from outright psychosis to secret evangelical missions of espionage and sabotage from inside the belly of the Beast. At least, that's the only meaning I can glean from statements such as "Wow, you'll really be able to do some good and effect some real change from the inside!" which I've heard over and over again from friends who couldn't fathom that I actually wanted to leave the Catholic Church just as I've found it, and yet join it wholeheartedly, anyway.

Sadly, it seems, our only response is one of forbearance. We can only nod and smile, and try not to take offense at the implications that we've lost our minds or don't read our Bibles. We can only hope and pray that, even if they never join us in our journey, they can at least be open to hearing about it, understanding our perspective, and prayerfully cheer us on, anyway. And, most of all, be sensitive to where they're at. You may not view your conversion as unfaithful consorting with the Whore of Babylon, but it might feel that way to your closest family members. For those who convert from Evangelicalism, as I did, the temptation to preach at your friends and family is overwhelming--but unless they're actually open to listening, you'll do more harm than good. The truth lived in loving silence is more powerful than truth spoken in pithy arguments. Or, as St. Francis of Assisi put it, "Preach the Gospel always, and when necessary, use words."

I'm praying for you all.

Please pray for me.

Gregory

Thursday, 25 February 2010

Tuesday, 5 January 2010

Sean Asks...Did God Really Knit Me Together in My Mother's Womb?

For thou didst form my inward parts,For many people, Psalm 139 is a beautiful hymn to God's glory and ever-present providential love. Knowing that He is so much a part of our lives, that He even carefully knit us together from the very moment of our conception brings a sense of comfort, wonder, awe, and even purpose to our lives.

thou didst knit me together in my mother's womb.

I praise thee, for thou art fearful and wonderful.

Wonderful are thy works!

Thou knowest me right well;

my frame was not hidden from thee,

when I was being made in secret,

intricately wrought in the depths of the earth.

Thy eyes beheld my unformed substance;

in thy book were written, every one of them,

the days that were formed for me,

when as yet there was none of them.

--Psalm 139:13-16

But such is not the case for everyone. When Sean asked me the question that forms the basis for this article, he admitted that this idea gave him a lot of trouble. He wrestled a lot with that passage in Psalm 139, about how God knits us together in our mothers' wombs. He said, "either that's not true, and the Bible has errors, or it is true and therefore God hates me. Because if He specifically put me in my mother's womb, that's the only logical conclusion."

In discussing this issue with Sean, I tried to provide alternative explanations--that God can use these problems for good, if Sean would let Him. That Sean could "offer up" his sufferings to Jesus for great spiritual and physical good for others, such as healings or conversions. And while the Church's teaching of "Redemptive Suffering" is true and good, and in very real ways has helped so many people recognise that there is a purpose to our suffering--that it is not in vain--nevertheless, the answers I had never seemed to quite get to the core of Sean's question--and the question behind the question, which was, at bottom, why did God put Sean inside that particular woman's womb? Beyond the unhelpful obvious, I had nothing.

Then one day we were discussing the Blessed Virgin Mary. Sean attends a Protestant church and, with the upcoming Christmas season, the pastor there felt that he had to say something about the Blessed Mother--which, as so often is the case, ends up being an anti-Catholic polemic against "Mariolatry". The pastor, in his sermon, basically denied (and misrepresented) Catholic interpretations of Mary, so Sean came right to me, and we began discussing it. Marian dogmas are difficult for him, as they are for most Protestants.

But all of a sudden he says to me, "I was thinking about Mary the other day, and all of a sudden I felt like I was in love. Not in a weird sexual way, but like she was the most perfect Lady and my Mother, all at the same time. I can't describe the feeling, but I still get all shy and blushing when I think about it--totally not like me!" (He is the lead singer in a rock band, after all.)

Sean and I had been discussing the Catholic Church's various teachings about Mary, and he had still felt somewhat uncomfortable about them. Yet doctrines are not the person that they describe. That is, the goal of the Christian life is not adherence to specific doctrinal formulations (although that is important and necessary). The Doctrines are there to point us to a person, and to lead us into relationship with that person. The Ultimate Goal is obviously to be led deeper into relationship with the Person of Jesus Christ. And yet that familial relationship with Jesus includes the rest of His family with it. Jesus, our Elder Brother, brings us into right relationship with His Father and our Father. And in His total self-giving, He give us all His family, too. Including His own Mother, whom He gave us at the Cross.

And Mary, true to her whole purpose for being, her one, truest love, leads us through a relationship with her, deeper in relationship, deeper in love, with God Himself.

So I said to Sean, "Remember how you said that if God knit you together in your mother's womb, then He must hate you? Does the fact that God gave you His own Mother help to make up for that?"

He was so overwhelmed by that he almost cried, and had to go offline just to meditate on that notion for a while. Mary brought healing to Sean's anger at God for the pain in his life because of his biological mother's abuse, and helped to mend a rift in Sean's relationship with Jesus.

God bless.

Friday, 11 December 2009

Mary, Mother of the World

Image © 2008 Gregory Watson

Oil on Canvas, monochrome (French Ultramarine Blue, Titanium White). 12" x 16".

This was the first project of my first year Oil Painting class at Mohawk College's Continuing Ed Creative Arts Certificate. I was originally going to title it somewhat tongue-in-cheek, "Sacre Bleu", but Melissa objected and retitled it Mary, Mother of the World.

The image is based somewhat on the "Miraculous Medal" image that Mary revealed to St. Catherine Labouré in 1830, as well as St. John's depiction of her in Revelation 12, clothed with the sun, standing on the moon, with a crown of twelve stars. She looks down from heaven with compassion on us, and showers us with the abundant graces she has received from Jesus.

I donated the original painting to my parish, St. Margaret Mary, to be raffled off in a youth group fundraiser. It was won by the youth minster, Nassrin Msiss, who assures me that the contest was not rigged, and that the prize-winners were drawn by objective third parties. Congrats, Nassrin!

Until I figure out how to set up PayPal with this site, please email doubting-thomist@hotmail.com to order Prints.

- Full size (12" x 16") limited edition high quality giclée print (unframed): $30.00 (CAD)

- Full size (12" x 16") limited edition high quality giclée print (framed): $60.00 (CAD)

- Image on 4¼" x 5½" Greeting Card (blank): $1.50 (CAD)

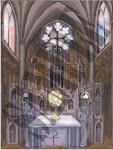

Adoration

Image © 2008 Gregory Watson

Oil on Canvas, limited palette (Permanent Alizarin Crimson, French Ultramarine Blue, Yellow Ochre, Titanium White). 12" x 16".

This was the second project of my first year Oil Painting class at Mohawk College's Continuing Ed Creative Arts Certificate. It was inspired by the main altar at St. Dunstan's Basilica in Charlottetown, PEI, based on a photo I had taken while vacationing there in 2007.

The title, Adoration, refers to the Catholic devotion of Eucharistic Adoration--the contemplative form of prayer engaged in while before the Eucharist exposed in a "monstrance", which is depicted on the altar in the painting.

I donated the original painting to my parish, St. Margaret Mary, to be raffled off in a youth group fundraiser. It was won by the parish priest, Fr. Bill Trusz, who claims that, for the amount of tickets he bought to win it, he deserves it! It's nice to have a fan! Congrats, Fr. Bill.

Until I figure out how to set up PayPal with this site, please email doubting-thomist@hotmail.com to order Prints.

- Full size (12" x 16") limited edition high quality giclée print (unframed): $30.00 (CAD)

- Full size (12" x 16") limited edition high quality giclée print (framed): $60.00 (CAD)

- Image on 4¼" x 5½" Greeting Card (blank): $1.50 (CAD)

Wednesday, 9 December 2009

Hadewijch of Antwerp's 7th Vision

Hadewijch of Antwerp was a "bequine", a form of lay religious common in the Middle Ages (after which modern lay orders were modelled), who likely lived c. 1250. She wrote about mystical experiences which she received during her reception of the Eucharist, and a deep, even "erotic" relationship with Jesus which she experienced in Communion. I reproduce this vision of hers as it directly relates to my previous post, Way Beyond "Personal Relationship"... Again, potentially not for the faint of heart.

One Pentecost at dawn I had a vision. Matins were being sung in the church and I was there. And my heart and my veins and all my limbs trembled and shuddered with desire. And I was in such a state as I had been so many times before, so passionate and so terribly unnerved that I thought I should not satisfy my Lover and my Lover not fully gratify me, then I would have to desire while dying and die while desiring. At that time I was so terribly unnerved with passionate love and in such pain that I imagined all my limbs breaking one by one and all my veins were separately in tortuous pain. The state of desire in which I then was cannot be expressed by any words or any person that I know. And even that which I could say of it would be incomprehensible to all who hadn't confessed this love by means of acts of passion and who were not known by Love. This much I can say about it: I desired to consummate my Lover completely and to confess and to savour in the fullest extent--to fulfil his humanity blissfully with mine and to experience mine therein, and to be strong and perfect so that I in turn would satisfy him perfectly: to be purely and exclusively and completely virtuous in every virtue. And to that end I wished, inside me, that he would satisfy me with his Godhead in one spirit (1 Cor 6:17) and he shall be all he is without restraint. For above all gifts I could choose, I choose that I may give satisfaction in all great sufferings. For that is what it means to satisfy completely: to grow to being god with God. For it is suffering and pain, sorrow and being in great new grieving, and letting this all come and go without grief, and to taste nothing of it but sweet love and embraces and kisses. Thus I desired that God should be with me so that I should be fulfilled together with him.

When at that time I was in a state of terrible weariness, I saw a great eagle, flying towards me from the altar. And he said to me: "If you wish to become one, then prepare yourself." And I fell to my knees and my heart longed terribly to worship that One Thing in accordance with its true dignity, which is impossible--I know that, God knows that, to my great sadness and burden. And the eagle turned, saying, "Righteous and most powerful Lord, show now the powerful force of your Unity for the consummation with the Oneness of yourself." And he turned back and said to me, "He who has come, comes again, and wherever he never came, there he will not come."

Then he came from the altar, showing himself as a child. And that child had the very same appearance that he had in his first three years. And he turned to me and from the ciborium he took his body in his right hand and in his left hand he took a chalice that seemed to come from the altar, but I know not where it came from. Thereupon he came in the appearance and the clothing of the man he was on that day when he first gave us his body, that appearance of a human being and a man, showing his sweet and beautiful and sorrowful face, and approaching me with the humility of the one who belongs entirely to another. Then he gave himself to me in the form of the sacrament, in the manner to which people are accustomed. Then he gave me to drink from the chalice in the manner and taste to which people are accustomed. Then he came to me himself and took me completely in his arms and pressed me to him. And all my limbs felt his limbs in the full satisfaction that my heart and my humanity desired. Then I was externally completely satisfied to the utmost satiation.

At that time I also had, for a short while, the strength to bear it. But all too soon I lost external sight of the shape of that beautiful man, and I saw him disappear to nothing, so quickly melting away and fusing together that I could not see or observe him outside of me, nor discern him within me. It was to me at that moment as if we were one without distinction. All of this was external, in sight, in taste, in touch, just as people may taste and see and touch receiving the external sacrament, just as a beloved may receive her lover in the full pleasure of seeing and hearing, with the one becoming one with the other. After this I remained in a state of oneness with my Beloved so that I melted into him and ceased to be myself. And I was transformed and absorbed in the spirit, and I had a vision about the following hours.

(From The Essential Writings of Christian Mysticism., Bernard McGinn, editor. Modern Library Classics, 2006. pp. 103-104.)

One Pentecost at dawn I had a vision. Matins were being sung in the church and I was there. And my heart and my veins and all my limbs trembled and shuddered with desire. And I was in such a state as I had been so many times before, so passionate and so terribly unnerved that I thought I should not satisfy my Lover and my Lover not fully gratify me, then I would have to desire while dying and die while desiring. At that time I was so terribly unnerved with passionate love and in such pain that I imagined all my limbs breaking one by one and all my veins were separately in tortuous pain. The state of desire in which I then was cannot be expressed by any words or any person that I know. And even that which I could say of it would be incomprehensible to all who hadn't confessed this love by means of acts of passion and who were not known by Love. This much I can say about it: I desired to consummate my Lover completely and to confess and to savour in the fullest extent--to fulfil his humanity blissfully with mine and to experience mine therein, and to be strong and perfect so that I in turn would satisfy him perfectly: to be purely and exclusively and completely virtuous in every virtue. And to that end I wished, inside me, that he would satisfy me with his Godhead in one spirit (1 Cor 6:17) and he shall be all he is without restraint. For above all gifts I could choose, I choose that I may give satisfaction in all great sufferings. For that is what it means to satisfy completely: to grow to being god with God. For it is suffering and pain, sorrow and being in great new grieving, and letting this all come and go without grief, and to taste nothing of it but sweet love and embraces and kisses. Thus I desired that God should be with me so that I should be fulfilled together with him.

When at that time I was in a state of terrible weariness, I saw a great eagle, flying towards me from the altar. And he said to me: "If you wish to become one, then prepare yourself." And I fell to my knees and my heart longed terribly to worship that One Thing in accordance with its true dignity, which is impossible--I know that, God knows that, to my great sadness and burden. And the eagle turned, saying, "Righteous and most powerful Lord, show now the powerful force of your Unity for the consummation with the Oneness of yourself." And he turned back and said to me, "He who has come, comes again, and wherever he never came, there he will not come."

Then he came from the altar, showing himself as a child. And that child had the very same appearance that he had in his first three years. And he turned to me and from the ciborium he took his body in his right hand and in his left hand he took a chalice that seemed to come from the altar, but I know not where it came from. Thereupon he came in the appearance and the clothing of the man he was on that day when he first gave us his body, that appearance of a human being and a man, showing his sweet and beautiful and sorrowful face, and approaching me with the humility of the one who belongs entirely to another. Then he gave himself to me in the form of the sacrament, in the manner to which people are accustomed. Then he gave me to drink from the chalice in the manner and taste to which people are accustomed. Then he came to me himself and took me completely in his arms and pressed me to him. And all my limbs felt his limbs in the full satisfaction that my heart and my humanity desired. Then I was externally completely satisfied to the utmost satiation.

At that time I also had, for a short while, the strength to bear it. But all too soon I lost external sight of the shape of that beautiful man, and I saw him disappear to nothing, so quickly melting away and fusing together that I could not see or observe him outside of me, nor discern him within me. It was to me at that moment as if we were one without distinction. All of this was external, in sight, in taste, in touch, just as people may taste and see and touch receiving the external sacrament, just as a beloved may receive her lover in the full pleasure of seeing and hearing, with the one becoming one with the other. After this I remained in a state of oneness with my Beloved so that I melted into him and ceased to be myself. And I was transformed and absorbed in the spirit, and I had a vision about the following hours.

(From The Essential Writings of Christian Mysticism., Bernard McGinn, editor. Modern Library Classics, 2006. pp. 103-104.)

Saturday, 5 December 2009

Way Beyond "Personal Relationship"...

(Warning: This post contains some mature themes pertaining to the Eucharist and Its relationship to us as "the Bride of Christ". I'd hesitate to let anyone 13 or younger read it without a parent's teaching presence.)

Since becoming a Catholic, I've encountered all sorts of criticism from well-meaning Christians who know that the main thing in Christianity is to have a "personal relationship" with Jesus. What they don't seem to know is that this relationship is available and encouraged in Catholicism. Many seem to think that the rituals and stuff stifles a free, spontaneous interaction with Jesus. Others claim that Mary and the Saints compete with Jesus and distract us from a relationship with Him. In fact, many people who leave the Catholic faith to become Protestant claim that they "weren't being fed," or "didn't ever hear the Gospel presented," or that they had never "asked Jesus into their heart." All these claims boil down to one simple statement: People believe that knowing Jesus personally is not the be all and end all of the Catholic Faith.

I'm here to say that that just ain't so.

All Christians will tell you that "God is everywhere." The more spiritually discerning will recognise that God, who is everywhere, will "concentrate" (for lack of a better word) His ubiquitous presence in a certain place at a certain time. After all, what else could Jesus mean when He claimed in Matthew 18:20, that "When two or three are gathered in My name, there I am in the midst of them"? If Jesus is always everywhere in the same manner and proportion, why promise to be especially with those gathered in His name?

Yet, even this special, spiritual presence of Christ is but a pale shadow of the reality and enormity of His Presence in every Catholic Church. For Jesus is not only present in some sort of intangible, mystical way, but He is as physically, locally present to us as He was to the disciples 2000 years ago, albeit in a different manner. I'll say it again: Jesus makes Himself physically present to us, Body, Blood, Soul, and Divinity! And He is always there, in the Church, in the Tabernacle, waiting for us and welcoming us! He may be spiritually present among us when two or three are gathered in His name; but He is physically present in the Tabernacle, whether any living soul is around or not! And just as with His Disciples so long ago, so now He "eagerly desires to celebrate the Passover" with us (cf. Luke 22:15).

For it is here, in our "Passover", that is, the Eucharistic Celebration of the Mass, that Jesus comes again to us, and meets with us in a most intimate way! He not only comes to dwell near us, or with us, but in our devout reception of the Eucharist, He comes to dwell physically, intimately, in us! No wonder, then, that Jesus' Real Presence in the Eucharist is called by the Church, "the source and summit of the Christian life" (CCC #1324). And it is precisely this that gives the lie to the objections that Jesus is not emphasised, or that no true relationship with Him exists in the Catholic Church.

There has been much criticism regarding modern "praise and worship" music that portrays our relationship with Jesus almost in terms of a love relationship. Songs are criticised as being such sappy love songs that if we substituted "baby" for "Jesus" it would be just another pop love song on the radio. As far as aesthetics go, I quite agree with the criticism. But the message? The problem is not with comparing our love with Jesus to romantic love. Let's remember that the monks and mystics of the Church since time immemorial have viewed our relationship with Jesus in the most graphic terms of intimacy. The favourite book of monasticism seems to have been Song of Solomon, which they interpreted allegorically as being about our relationship with Jesus! Nothing in popular praise and worship songs rivals the erotic poetry of Solomon. In fact, the problem with most of these (Protestant) songs is that they are incomplete expressions of that fullness of intimacy. It is, to put it bluntly, singing about going all the way, when you've only ever made it to first or second base!

Modern scholars often are heard accusing the monks of "twisting" the Song of Songs into this allegorical meaning because they couldn't bear the thought of sex being so glorified in Sacred Scripture. What these modern scholars fail to realise, is that every monk knew that the key to understanding the allegorical meaning of Scripture was to base it on the literal meaning. They knew good and well that the Song of Solomon was a poem of unbridled eroticism celebrating the consummation of marriage! And it was from this understanding that they grew to understand the deeper meaning of our intimacy with Christ.

The reason modern scholars fail to grasp this, I submit, is that modern scholars have not experienced that deeper intimacy with Christ. Bluntly, there is more than metaphor going on in the Bible's description of the Church as the "bride of Christ"; and it is more than linguistic accident that that first marital act of sexual intercourse is known by the same term as the act of partaking of the Eucharistic Body of Our Lord: Consummation.

In first century Jewish culture, a man would betroth a woman in a legally binding covenant. For all intents and purposes, the couple was "married", and could share in all the "attendant privileges" of marriage. However, despite this, the betrothal period usually lasted about a year, because the groom had to "prepare a place" for his bride to live in his family's home. This preparation included both the physical living arrangements, as well as his establishment as provider. At the Last Supper with His Disciples, Jesus inaugurated the "New Covenant" in His blood (cf. Luke 22:20). It was through this Covenant that He betrothed His Church, and He specifically used language to convey that point, when He said, "Do not let your hearts be troubled. You trust in God, trust also in Me. In My Father's house there are many places to live in; otherwise I would not have told you. I am going now to prepare a place for you, and after I have gone and prepared you a place, I shall return to take you to Myself, so that you may be with Me where I am" (John 14:1-3, emphasis mine). This is the same formula as the marriage covenant that I discussed above! It's little wonder that Thomas and the other disciples were confused by Jesus' words! In their minds, the marriage connotations would have stood out, but not really made a lot of sense until later.

Thus, we are in the betrothal period, until the return of Jesus, when He will take us up to the Heavenly Wedding Feast! In the meantime, He comes to us, as the first century Jewish groom, and shares with us the intimacy of married life in the interim. The monks and nuns were not wrong in viewing themselves as "married" to Christ. They live in an extreme and symbolic way the marriage with Jesus to which we are all called, and in which we all participate in the Consummation of His Real Presence in the Eucharistic Host. And as in all such unions, the purpose is to "be fruitful and multiply," as Jesus Himself teaches us, when He continues the conversation at the Last Supper, telling us that we must abide in Him, and He in us, so that we can bear much fruit. And it is in the Eucharist (the Vine, of which we are the branches) that we achieve this abiding state. For Jesus is not only present to us in the celebration of the Mass--but He remains there, afterwards, in the Tabernacle, calling us to spend time in His Presence, in Adoration before the Tabernacle or the Monstrance. And as we leave, His Eucharistic Presence within us, we are filled with His grace, and transformed ever more into His likeness--that we too can become His monstrances to the world!

Why settle for first base, when Jesus calls us to go all the way?

Since becoming a Catholic, I've encountered all sorts of criticism from well-meaning Christians who know that the main thing in Christianity is to have a "personal relationship" with Jesus. What they don't seem to know is that this relationship is available and encouraged in Catholicism. Many seem to think that the rituals and stuff stifles a free, spontaneous interaction with Jesus. Others claim that Mary and the Saints compete with Jesus and distract us from a relationship with Him. In fact, many people who leave the Catholic faith to become Protestant claim that they "weren't being fed," or "didn't ever hear the Gospel presented," or that they had never "asked Jesus into their heart." All these claims boil down to one simple statement: People believe that knowing Jesus personally is not the be all and end all of the Catholic Faith.

I'm here to say that that just ain't so.

All Christians will tell you that "God is everywhere." The more spiritually discerning will recognise that God, who is everywhere, will "concentrate" (for lack of a better word) His ubiquitous presence in a certain place at a certain time. After all, what else could Jesus mean when He claimed in Matthew 18:20, that "When two or three are gathered in My name, there I am in the midst of them"? If Jesus is always everywhere in the same manner and proportion, why promise to be especially with those gathered in His name?

Yet, even this special, spiritual presence of Christ is but a pale shadow of the reality and enormity of His Presence in every Catholic Church. For Jesus is not only present in some sort of intangible, mystical way, but He is as physically, locally present to us as He was to the disciples 2000 years ago, albeit in a different manner. I'll say it again: Jesus makes Himself physically present to us, Body, Blood, Soul, and Divinity! And He is always there, in the Church, in the Tabernacle, waiting for us and welcoming us! He may be spiritually present among us when two or three are gathered in His name; but He is physically present in the Tabernacle, whether any living soul is around or not! And just as with His Disciples so long ago, so now He "eagerly desires to celebrate the Passover" with us (cf. Luke 22:15).

For it is here, in our "Passover", that is, the Eucharistic Celebration of the Mass, that Jesus comes again to us, and meets with us in a most intimate way! He not only comes to dwell near us, or with us, but in our devout reception of the Eucharist, He comes to dwell physically, intimately, in us! No wonder, then, that Jesus' Real Presence in the Eucharist is called by the Church, "the source and summit of the Christian life" (CCC #1324). And it is precisely this that gives the lie to the objections that Jesus is not emphasised, or that no true relationship with Him exists in the Catholic Church.

There has been much criticism regarding modern "praise and worship" music that portrays our relationship with Jesus almost in terms of a love relationship. Songs are criticised as being such sappy love songs that if we substituted "baby" for "Jesus" it would be just another pop love song on the radio. As far as aesthetics go, I quite agree with the criticism. But the message? The problem is not with comparing our love with Jesus to romantic love. Let's remember that the monks and mystics of the Church since time immemorial have viewed our relationship with Jesus in the most graphic terms of intimacy. The favourite book of monasticism seems to have been Song of Solomon, which they interpreted allegorically as being about our relationship with Jesus! Nothing in popular praise and worship songs rivals the erotic poetry of Solomon. In fact, the problem with most of these (Protestant) songs is that they are incomplete expressions of that fullness of intimacy. It is, to put it bluntly, singing about going all the way, when you've only ever made it to first or second base!

Modern scholars often are heard accusing the monks of "twisting" the Song of Songs into this allegorical meaning because they couldn't bear the thought of sex being so glorified in Sacred Scripture. What these modern scholars fail to realise, is that every monk knew that the key to understanding the allegorical meaning of Scripture was to base it on the literal meaning. They knew good and well that the Song of Solomon was a poem of unbridled eroticism celebrating the consummation of marriage! And it was from this understanding that they grew to understand the deeper meaning of our intimacy with Christ.

The reason modern scholars fail to grasp this, I submit, is that modern scholars have not experienced that deeper intimacy with Christ. Bluntly, there is more than metaphor going on in the Bible's description of the Church as the "bride of Christ"; and it is more than linguistic accident that that first marital act of sexual intercourse is known by the same term as the act of partaking of the Eucharistic Body of Our Lord: Consummation.

In first century Jewish culture, a man would betroth a woman in a legally binding covenant. For all intents and purposes, the couple was "married", and could share in all the "attendant privileges" of marriage. However, despite this, the betrothal period usually lasted about a year, because the groom had to "prepare a place" for his bride to live in his family's home. This preparation included both the physical living arrangements, as well as his establishment as provider. At the Last Supper with His Disciples, Jesus inaugurated the "New Covenant" in His blood (cf. Luke 22:20). It was through this Covenant that He betrothed His Church, and He specifically used language to convey that point, when He said, "Do not let your hearts be troubled. You trust in God, trust also in Me. In My Father's house there are many places to live in; otherwise I would not have told you. I am going now to prepare a place for you, and after I have gone and prepared you a place, I shall return to take you to Myself, so that you may be with Me where I am" (John 14:1-3, emphasis mine). This is the same formula as the marriage covenant that I discussed above! It's little wonder that Thomas and the other disciples were confused by Jesus' words! In their minds, the marriage connotations would have stood out, but not really made a lot of sense until later.

Thus, we are in the betrothal period, until the return of Jesus, when He will take us up to the Heavenly Wedding Feast! In the meantime, He comes to us, as the first century Jewish groom, and shares with us the intimacy of married life in the interim. The monks and nuns were not wrong in viewing themselves as "married" to Christ. They live in an extreme and symbolic way the marriage with Jesus to which we are all called, and in which we all participate in the Consummation of His Real Presence in the Eucharistic Host. And as in all such unions, the purpose is to "be fruitful and multiply," as Jesus Himself teaches us, when He continues the conversation at the Last Supper, telling us that we must abide in Him, and He in us, so that we can bear much fruit. And it is in the Eucharist (the Vine, of which we are the branches) that we achieve this abiding state. For Jesus is not only present to us in the celebration of the Mass--but He remains there, afterwards, in the Tabernacle, calling us to spend time in His Presence, in Adoration before the Tabernacle or the Monstrance. And as we leave, His Eucharistic Presence within us, we are filled with His grace, and transformed ever more into His likeness--that we too can become His monstrances to the world!

Why settle for first base, when Jesus calls us to go all the way?

Tuesday, 17 November 2009

Sean Asks... About Forgiveness

As I mentioned in my Welcome post, this blog was born out of an ongoing relationship with a friend named Sean, who has asked me many insightful questions about the nature of God and Christian faith. His satisfaction with my answers led him to believe that those answers, and others that I might be able to provide, could benefit other people in similar situations of questioning or doubt. With this post, I'll be beginning a regular "series" revisiting the questions that Sean has asked me over the past year or so (at least as many as both of us can remember). It will be labelled in the sidebar as "Sean Asks..." I hope my answers might help you as much as they helped him.

Oh, and just a note about the Q&A forums--just because I put a new post up doesn't mean you can't still ask questions in them. To find them easily, click QnA in the sidebar.

Sean asked me once about the topic of forgiveness. Particularly, he was troubled by the fact that God seems to ask us to forgive other people no matter what--even if they never ask for it or do anything worthy of our forgiveness; but God Himself does not forgive us in a similar manner. Rather, He withholds forgiveness until we have suitably repented of our sins. To Sean, this seemed unjust--that God would demand something of us (indeed, hinge our own forgiveness on it--Matt 6:14-15) that He Himself is not willing to do.

In order to answer Sean's question, we have to look at what Forgiveness is, how God forgives us, and finally, how God requires us to forgive. For I think many of us have a somewhat skewed notion of these things.

Forgiveness, first of all, does not mean ignoring a problem with another person, pretending it didn't happen, or that it didn't really matter. We often hear that we are to "forgive and forget." However, it seems to me that one is a choice, while the other is not. Unless my wife sustains a severe head injury, she not likely to forget that a friend of mine gravely and unfairly insulted her. Now, my wife, full of grace and compassion, may choose to forgive my friend, whether my friend asks or not. But she will for ever after be rather wary around my friend, lest she should be hurt again.

Forgetting would, in all honesty, be rather naïve. Consider the example I gave to Sean: If his children were molested by a paedophile, by the sheer grace of God, Sean might one day come to forgive the offender. Despite that choice, Sean would be incredibly foolish to ever let his children be in the man's company again.

If forgiveness is not simply forgetting about our hurt, or pretending that it never happened, or that it didn't really matter, then what is it? What is Jesus commanding us to do, in telling us to forgive another's failings towards us, even if they don't ask for it or don't deserve it? I believe it is this: When we forgive, we let go of our right to punish or avenge the wrong done to us. This does not mean that the wrong never occurred, or that the harm has been diminished; it does not let the offender off the hook, so to speak. Rather, it keeps us from ending up on the same hook, ourselves. Forgiveness is humbly acknowledging that we don't know the whole story. Because of this, our judgement will never be fully just. Only God, who knows everything, knows exactly what the offender deserves. When we forgive, we are surrendering our bitterness, our hatred, however valid, to God. We make an act of trust in the goodness of God, that He will judge fairly, and that we will be vindicated.

That, as hard as it is, is actually the easy part of forgiveness. But there is one more aspect. When we forgive, we make a choice to be willing to reconcile with the offending party. That is, if the other person never repents or apologises to us, never tries to make amends, we nevertheless must hold out hope for that possibility. And more, should that opportunity arise, forgiveness means that we embrace it, and that we do, in fact, reconcile. As with pretty much everything else that God calls us to do, forgiveness and reconciliation can only be accomplished through God's grace at work in us. So don't be discouraged if you read this, and think, "I could never do that!" It's true--on your own, you certainly can't. I certainly can't! But as Scripture says, "There is nothing I cannot do in the One who strengthens me" (Philippians 4:13). The key is, though, we have to cooperate with that grace. We have to ask for it, and when God grants it, we have to act on it. Forgiveness is ultimately an act of surrender.

This leads to the second part of the answer to Sean's question: Is God's method of forgiveness contrary to what He asks of us? The short answer, I believe, is "no." We often speak of needing to repent in order to be forgiven by God, and in a sense, this is true. However, I believe that sense is best labelled "synechdoche". Synechdoche is one of those fun obscure literary terms that one learns about in high school English, in the poetry unit (I believe I first encountered it in Grade 10). It means to substitute a part for the whole, such as when we refer to the Sacred Heart of Jesus--we're not adoring only His heart, but all of Him, summed up by the symbol of His Heart, imaging His great love for us. Or, it's like when we tell someone to "take the wheel". We aren't saying that they should only use the steering wheel when driving our car. They "take" the pedals, the gear shift, the signal lever, and, quite frankly, the whole car.

Thus, I submit that when the Bible says "Repent and be baptised for the forgiveness of your sins" (cf. Acts 2:38), it is using "forgiveness" in a synechdochous fashion for the whole process of our reconciliation with God. It does not mean that God is unwilling to forgive us, or hasn't provided the way for our forgiveness, until that moment when we turn to Him. Rather, God has forgiven us in an analogous sense to that which He asks of us. Namely, He sent His Son into the world to die for us, to purchase our salvation, in order that the debt of our sins could be forgiven. He's made our forgiveness possible, and, as such, has "forgiven" us, just as we forgive our enemies by surrendering our bitterness to God and allowing Him to be the just judge, and not we ourselves.

But, just as our personal act of surrender, that act of forgiveness, is incomplete without participation from our enemy--that is, if the offender never apologises and makes reparation for his offences, there is no actual reconciliation between us--so too must we, the offenders of God's Law, turn to Him with contrition and apologise for our sins. We must do penance to demonstrate that we are indeed sorry and want to make it up to Him. Now, of course, just as with our attempt to forgive, our attempt to atone is fruitless unless it is empowered by God's grace. But the small acts of penance are our cooperation with that grace, and, empowered by grace, do actually merit that atonement, that reconciliation, for us.

So, we see that God has forgiven us before we repented--that is, as St. Paul says, "while we were enemies, we were reconciled to God through the death of His Son" (Romans 5:10), or, as St. John tells us, "Love consists in this: it is not we who loved God, but God loved us and sent His Son to expiate our sins. My dear friends, if God loved us so much, we too should love one another" (1 John 4:10-11). However, in order to receive that forgiveness, we must indeed turn to Him with sorrow for our sins, and "produce fruit in keeping with repentance" (Luke 3:8).

Through baptism, our sins up to that point are washed away. Our further sins are forgiven through their sorrowful confession, and the acts of penance, in the sacrament of Reconciliation. God has made this possible through Jesus Christ, who, ministering through the priest, absolves us and reconciles us to Him. But we don't benefit unless we participate.

So too, God calls us to forgive our enemies, as He has forgiven us already while we were still His enemies. Whether our enemies ever come to reconcile with us is ultimately between them and God. Through our forgiving, we have surrendered the need to judge them to Him, the rightful and just Judge. And, if by the grace of God, they do come to us repentant, then we are called to offer them the gift of reconciliation, just as God freely gives us that gift as often as we need it and seek it.

Now that you've read this, please remember that I said I'd do my best to give you the answer. I never said you'd like the answer I give you :) Jesus didn't say that following Him would involve dying to ourselves for nothing! But the emblem of our faith, the Crucifix, reminds us once more that God doesn't ask us to do anything that He wasn't willing to do for us already.

God bless

Gregory

Oh, and just a note about the Q&A forums--just because I put a new post up doesn't mean you can't still ask questions in them. To find them easily, click QnA in the sidebar.

Sean asked me once about the topic of forgiveness. Particularly, he was troubled by the fact that God seems to ask us to forgive other people no matter what--even if they never ask for it or do anything worthy of our forgiveness; but God Himself does not forgive us in a similar manner. Rather, He withholds forgiveness until we have suitably repented of our sins. To Sean, this seemed unjust--that God would demand something of us (indeed, hinge our own forgiveness on it--Matt 6:14-15) that He Himself is not willing to do.

In order to answer Sean's question, we have to look at what Forgiveness is, how God forgives us, and finally, how God requires us to forgive. For I think many of us have a somewhat skewed notion of these things.

Forgiveness, first of all, does not mean ignoring a problem with another person, pretending it didn't happen, or that it didn't really matter. We often hear that we are to "forgive and forget." However, it seems to me that one is a choice, while the other is not. Unless my wife sustains a severe head injury, she not likely to forget that a friend of mine gravely and unfairly insulted her. Now, my wife, full of grace and compassion, may choose to forgive my friend, whether my friend asks or not. But she will for ever after be rather wary around my friend, lest she should be hurt again.

Forgetting would, in all honesty, be rather naïve. Consider the example I gave to Sean: If his children were molested by a paedophile, by the sheer grace of God, Sean might one day come to forgive the offender. Despite that choice, Sean would be incredibly foolish to ever let his children be in the man's company again.

If forgiveness is not simply forgetting about our hurt, or pretending that it never happened, or that it didn't really matter, then what is it? What is Jesus commanding us to do, in telling us to forgive another's failings towards us, even if they don't ask for it or don't deserve it? I believe it is this: When we forgive, we let go of our right to punish or avenge the wrong done to us. This does not mean that the wrong never occurred, or that the harm has been diminished; it does not let the offender off the hook, so to speak. Rather, it keeps us from ending up on the same hook, ourselves. Forgiveness is humbly acknowledging that we don't know the whole story. Because of this, our judgement will never be fully just. Only God, who knows everything, knows exactly what the offender deserves. When we forgive, we are surrendering our bitterness, our hatred, however valid, to God. We make an act of trust in the goodness of God, that He will judge fairly, and that we will be vindicated.

That, as hard as it is, is actually the easy part of forgiveness. But there is one more aspect. When we forgive, we make a choice to be willing to reconcile with the offending party. That is, if the other person never repents or apologises to us, never tries to make amends, we nevertheless must hold out hope for that possibility. And more, should that opportunity arise, forgiveness means that we embrace it, and that we do, in fact, reconcile. As with pretty much everything else that God calls us to do, forgiveness and reconciliation can only be accomplished through God's grace at work in us. So don't be discouraged if you read this, and think, "I could never do that!" It's true--on your own, you certainly can't. I certainly can't! But as Scripture says, "There is nothing I cannot do in the One who strengthens me" (Philippians 4:13). The key is, though, we have to cooperate with that grace. We have to ask for it, and when God grants it, we have to act on it. Forgiveness is ultimately an act of surrender.

This leads to the second part of the answer to Sean's question: Is God's method of forgiveness contrary to what He asks of us? The short answer, I believe, is "no." We often speak of needing to repent in order to be forgiven by God, and in a sense, this is true. However, I believe that sense is best labelled "synechdoche". Synechdoche is one of those fun obscure literary terms that one learns about in high school English, in the poetry unit (I believe I first encountered it in Grade 10). It means to substitute a part for the whole, such as when we refer to the Sacred Heart of Jesus--we're not adoring only His heart, but all of Him, summed up by the symbol of His Heart, imaging His great love for us. Or, it's like when we tell someone to "take the wheel". We aren't saying that they should only use the steering wheel when driving our car. They "take" the pedals, the gear shift, the signal lever, and, quite frankly, the whole car.

Thus, I submit that when the Bible says "Repent and be baptised for the forgiveness of your sins" (cf. Acts 2:38), it is using "forgiveness" in a synechdochous fashion for the whole process of our reconciliation with God. It does not mean that God is unwilling to forgive us, or hasn't provided the way for our forgiveness, until that moment when we turn to Him. Rather, God has forgiven us in an analogous sense to that which He asks of us. Namely, He sent His Son into the world to die for us, to purchase our salvation, in order that the debt of our sins could be forgiven. He's made our forgiveness possible, and, as such, has "forgiven" us, just as we forgive our enemies by surrendering our bitterness to God and allowing Him to be the just judge, and not we ourselves.

But, just as our personal act of surrender, that act of forgiveness, is incomplete without participation from our enemy--that is, if the offender never apologises and makes reparation for his offences, there is no actual reconciliation between us--so too must we, the offenders of God's Law, turn to Him with contrition and apologise for our sins. We must do penance to demonstrate that we are indeed sorry and want to make it up to Him. Now, of course, just as with our attempt to forgive, our attempt to atone is fruitless unless it is empowered by God's grace. But the small acts of penance are our cooperation with that grace, and, empowered by grace, do actually merit that atonement, that reconciliation, for us.

So, we see that God has forgiven us before we repented--that is, as St. Paul says, "while we were enemies, we were reconciled to God through the death of His Son" (Romans 5:10), or, as St. John tells us, "Love consists in this: it is not we who loved God, but God loved us and sent His Son to expiate our sins. My dear friends, if God loved us so much, we too should love one another" (1 John 4:10-11). However, in order to receive that forgiveness, we must indeed turn to Him with sorrow for our sins, and "produce fruit in keeping with repentance" (Luke 3:8).

Through baptism, our sins up to that point are washed away. Our further sins are forgiven through their sorrowful confession, and the acts of penance, in the sacrament of Reconciliation. God has made this possible through Jesus Christ, who, ministering through the priest, absolves us and reconciles us to Him. But we don't benefit unless we participate.

So too, God calls us to forgive our enemies, as He has forgiven us already while we were still His enemies. Whether our enemies ever come to reconcile with us is ultimately between them and God. Through our forgiving, we have surrendered the need to judge them to Him, the rightful and just Judge. And, if by the grace of God, they do come to us repentant, then we are called to offer them the gift of reconciliation, just as God freely gives us that gift as often as we need it and seek it.

Now that you've read this, please remember that I said I'd do my best to give you the answer. I never said you'd like the answer I give you :) Jesus didn't say that following Him would involve dying to ourselves for nothing! But the emblem of our faith, the Crucifix, reminds us once more that God doesn't ask us to do anything that He wasn't willing to do for us already.

God bless

Gregory

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)